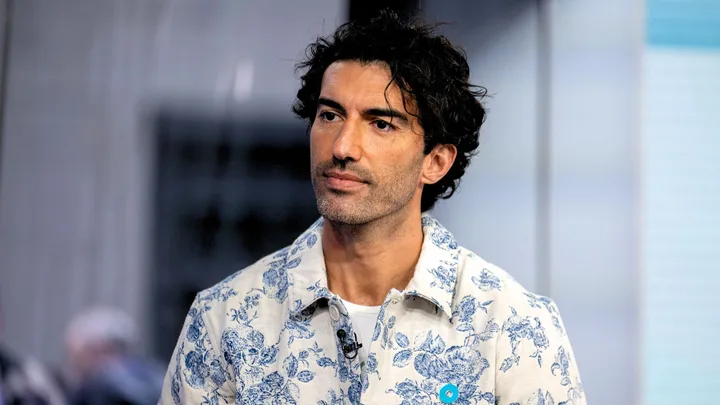

Hello everyone, I’m Britney Lewis, a breaking news reporter here at Forbes, and today we’re diving into the details of a legal battle involving Hollywood actor and producer Justin Baldoni. Joining me is Kevin Goldberg, Vice President and First Amendment expert at Freedom Forum, to break down the lawsuit he’s filed against The New York Times. Kevin, thank you so much for being here!

Kevin Goldberg: Thanks for having me! I’m excited to dive into this complex case.

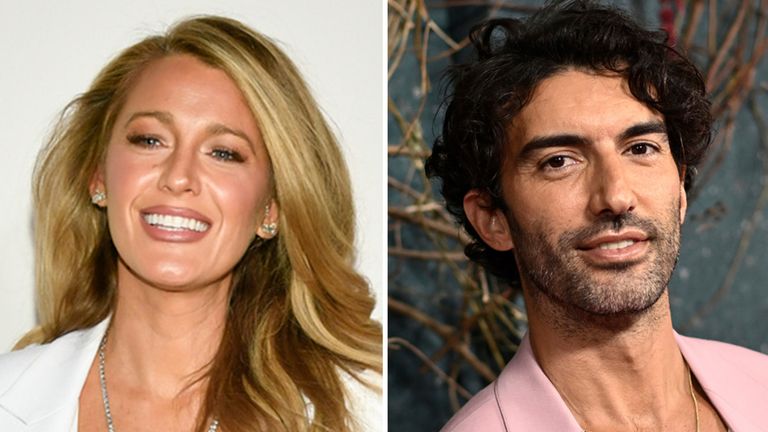

The lawsuit has drawn significant attention, particularly in the wake of an article from The New York Times that covered allegations of sexual harassment and a smear campaign involving Baldoni. Let’s break this down for our viewers. Before Christmas, Blake Lively filed a complaint in California, accusing Justin Baldoni of orchestrating a smear campaign against her. Then, shortly after New Year’s, Lively filed a lawsuit in New York federal court, claiming retaliation for reporting sexual harassment and safety concerns.

On the same day, Baldoni responded by filing a lawsuit against The New York Times, alleging defamation and other charges, totaling up to $250 million. Kevin, from a legal standpoint, what stands out to you in this timeline of events?

Kevin Goldberg: Well, as you mentioned, this is a significant legal development. But what stands out to me, especially from a First Amendment perspective, is the defamation lawsuit filed by Justin Baldoni against The New York Times. This lawsuit, which is 90 pages long, alleges multiple claims including defamation, false light, and invasion of privacy. The key here is the “actual malice” standard, which is extremely high when it comes to defamation lawsuits filed by public figures like Bdoni

Public figures must show that the statements made about them were false, published with acal malice, and caused actual harm. “Actual malice” is the crucial term here. It means the paper knowingly published false information or acted with reckless disregard for the truth.

What’s In the Lawsuit? The lawsuit focuses a lot on factual recitations, especially related to text messages and communications between Baldoni and others. Kevin, what do you make of the details in the complaint, and does Baldoni have a strong case?

Kevin Goldberg: It’s definitely a lengthy and fact-heavy complaint. Much of it focuses on specific communications, like text messages, and how The New York Times might have selectively used these details in their coverage. What stands out here is the claim that the Times omitted certain crucial information, which could have changed the meaning of the messages.

In defamation cases involving public figures, the burden is on the plaintiff to prove that the press acted with actual malice. This lawsuit argues that by cherry-picking messages, The New York Times intentionally misled the public. If they can prove that the paper acted with reckless disregard for the truth, it could make for a compelling case.

The Upside-Down Smiley Face: A Key Detail? A central element in the lawsuit is the omission of an upside-down smiley face from a key text message. The complaint argues that this emoji, which is often used to convey sarcasm or irony, was crucial for understanding the true intent of the message. Kevin, do you think this omission is significant enough to show actual malice?

Kevin Goldberg: That’s a very interesting point. The inclusion or omission of such a small detail could have a big impact. The lawsuit suggests that by leaving out the upside-down smiley face, The New York Times misrepresented the message, changing its meaning. If the paper knew this detail was important and chose to omit it, it could show that they acted with malice or at least with reckless disregard for the truth.

In defamation cases, it’s not just about what was published; it’s also about what was left out. If The New York Times selectively chose facts to suit their narrative, that could be crucial evidence of actual malice.

Is There a Strong Case? At the heart of Baldoni’s lawsuit is the argument that The New York Times acted with malice by publishing a distorted version of the events. This is where things get tricky, because in defamation cases involving public figures, the standard is so high. Does Baldoni’s lawsuit make a strong case, Kevin?

Kevin Goldberg: The burden of proof is certainly high in these cases. To win, Baldoni would need to prove that The New York Times published false information with the knowledge that it was wrong or with a reckless disregard for the truth. The complaint’s focus on omissions—like the upside-down smiley face—could be key in proving malice. If Baldoni’s team can show that the omissions were intended to mislead, or if the paper acted recklessly, it could tip the scales in their favor.

However, defamation lawsuits against the media are notoriously difficult to win, especially when they involve public figures. The fact that The New York Times is a highly reputable media outlet also makes it more challenging for Baldoni to meet the actual malice standard.

Conclusion: This lawsuit is a fascinating legal battle that could have far-reaching consequences, not just for Justin Baldoni and The New York Times, but for defamation law in general. Public figures face an uphill battle when suing the press for defamation, but if Baldoni’s legal team can prove that the Times acted with actual malice, it could be a game-changer.

Kevin Goldberg: Absolutely, this case is one to watch. It’ll be interesting to see how the courts interpret the issue of “actual malice” and whether they will hold the press accountable for the way they report on sensitive matters.

Thank you so much, Kevin, for joining me today and offering your expert legal insights. It’s certainly a case that will continue to develop, and we’ll be sure to keep following it closely. Stay tuned for more updates on this unfolding legal drama.